Posted in San Juan Islander: 1 Jun 2015 — By Laura Newcomb

As you walk past the Kings Market seafood aisle in Friday Harbor or browse at Costco, chances are that you will see fresh mussels harvested locally from Penn Cove Shellfish on Whidbey Island, WA. These mussels have been cleaned and washed to look enticing to buy, cook, and eat. What you do not see when you look at these mussels is one of the most important parts: the byssal threads that attached the mussels to the lines they grew on (Figure 1), enabling them to then progress from the ocean to your plate.

Fig. 1: Mussels attached to each other with their byssal threads. Photo credit: E. Carrington.

Mussels are the Spidermen of the sea: they mold byssal threads to attach to a variety of surfaces, from rocks to aquaculture lines. These threads act as stretchy tethers to keep a mussel in place (Bell and Gosline, 1996). The mussel aquaculture industry takes advantage of this characteristic in their farming practices. Adult mussels living along the shores of Penn Cove release egg and sperm into the water column, a process known as mass spawning. When egg and sperm collide, the egg is fertilized and the larva begins to grow. During this phase, larvae swim around in the currents, feeding and looking for a good home to settle and attach with their first adult byssal threads. Penn Cove Shellfish puts out collector lines in early spring (April – May) to catch this mussel “seed.” Mussels then grow right on these collector lines for about one year, until they reach harvestable size (Figures 2 and 3).

Fig. 2: Penn Cove Shellfish mussel harvesting boat tied up to a mussel raft.Photo credit: E. Carrington.

The problem arises when the mussels fall off, leaving the lines bare. Mussel fall-off due to seasonally weak attachment and increased storm action is a process mussels encounter on rocky shores (Paine and Levin, 1981). A mussel becomes weakly attached when it produces fewer or poor quality individual byssal threads, making the animal more likely to dislodge under waves and currents. Mussel fall-off cuts into a grower’s yield at harvest and is a problem for the industry worldwide.

With funding support from Washington Sea Grant and the National Science Foundation, a team led by Dr. Emily Carrington and including Dr. Carolyn Friedman, Dr. Michael (Moose) O’Donnell, Penn Cove Shellfish General Manager Ian Jefferds, Biology graduate students Matt George, Molly Roberts, and Laura Newcomb have set out to address this problem. Our work seeks to identify what environmental factors may trigger weakened mussel attachment in farmed mussels. We started in the laboratory by identifying two potential culprits to test, ocean acidification and ocean warming. Using controlled experimental mesocosms (aka fancy Igloo coolers) in Friday Harbor Laboratories’ Ocean Acidification Environmental Laboratory (FHL OAEL), we exposed mussels to a range of conditions to identify the threshold values for weakening: pH below 7.6 (O’Donnell et al. 2013) and temperature above 19˚C (66˚F). We also learned that elevated temperature reduces the number of threads a mussel makes, further weakening whole mussel attachment.

Fig. 3: Mussel aquaculture lines hanging in the water at Penn Cove. Photo credit: E. Carrington.

With the lab experiments identifying pH and temperature as possible weakening agents, we moved out to a mussel farm to ask if mussels ever encounter these threshold conditions and if so, do these events coincide with weak mussel attachment?

Partnering with Penn Cove Shellfish (the oldest and largest mussel farm in the nation), we installed multi-parameter instruments in Penn Cove on Whidbey Island to log hourly measurements of seawater temperature and pH, as well as salinity, dissolved oxygen, and chlorophyll. These data are uploaded onto the internet in real time (http://nvs.nanoos.org/Explorer) so that we (and anyone else) can check in to see what the conditions are like at any time (Figure 4).

Growers hang mussel lines vertically in the water at depths from 1 to 7m, so we placed our sensor arrays at those depths to capture conditions throughout the water column. This equipment has been in place and logging since late summer 2014. So far, we have found summer water temperatures at 1m can surpass the 19˚C (66˚F) threshold for a few hours on warm days and pH dips below the threshold of 7.6, with especially prolonged periods from October – February at both 1 and 7m. These measurements tell us that mussels do experience conditions that can weaken their attachment, and our concern is that these conditions are projected to get worse over the next 100 years.

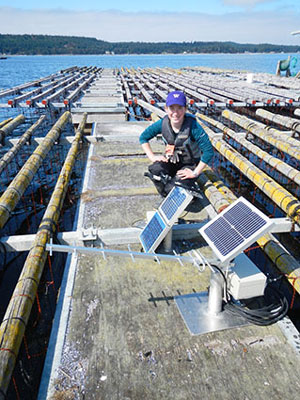

Fig. 4: Laura Newcomb with solar-powered telemetry units on a mussel harvesting raft, transferring the water temperature and pH measurements to the internet. Photo credit: E. Carrington.

At this point in the study, we don’t quite have enough monthly measurements of mussel attachment at 1 and 7m to fully evaluate how pH and high temperature may be affecting mussels in the field. However, we have observed that mussels are weaker in the months when the maximum temperature exceeds 18˚C. This observation suggests temperature may act as an environmental trigger for weak attachment. We are continuing to measure mussels and water conditions and will soon be able to firm up our conclusions about the effects of temperature and pH on mussels at the farm.

Moving our research from the lab to the field has allowed us to extend our results to an industry that stands to be affected by changing ocean conditions. By installing sensors that monitor the water in real time, we hope to give mussel farmers an early warning system for conditions that could threaten their mussels. Recently we have expanded our studies to include Penn Cove Shellfish’s farm in Quilcene Bay, WA, made possible by our partnership with Washington State Department of Natural Resources. We are excited our collaborative research can contribute to sustaining a culturally and economically important resource for Washington State – and keep this popular seafood in grocery stores for years to come (Figure 5).

Fig. 5: Dr. Emily Carrington (left) meeting with Washington Gov. Jay Inslee (right) at Penn Cove Shellfish to discuss how ocean acidification could affect mussel farms, with Biology graduate student Molly Roberts in the back right.Photo credit: I. Jefferds.

Laura Newcomb is a PhD candidate in UW’s Department of Biology under advisor Emily Carrington.