By Climate Guest Blogger on Sep 14, 2011 — by Kiley Kroh

Americans consume approximately 700 million farmed oysters per year. Despite our love for these briny bivalves, shellfish and the coastal communities that depend on them face serious threats.

In a recent piece, Eric Scigliano examines “The Great Oyster Crash” of 2007, in which oyster seed (larvae) off the coast of Oregon and Washington began dying by the millions, seemingly without cause. After taking aggressive measures to eliminate bacteria in the tanks, and failing to halt their losses, the owners began to suspect the problem was a more fundamental change in the makeup of the oceans. With the help of local scientists, they found that their losses were directly linked to a far more ominous phenomenon: ocean acidification.

As Scigliano explains, “the oceans are the world’s great carbon sink, holding about 50 times as much of the element as the air.” As carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels and other industrial processes rise, so too does the level of acidity in the oceans. Once it reaches a certain threshold, ocean acidification becomes lethal to many species, including clams and oysters, which become unable to build the shells or skeletons they need to survive.

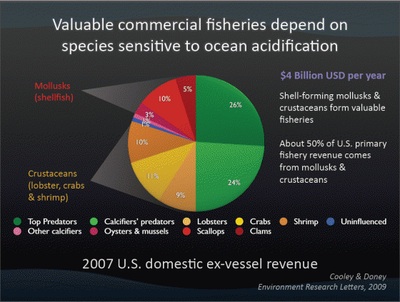

The rise in acidity and subsequent oyster crash took a significant toll on coastal communities – from 2005 to 2009, West Coast production dropped from 93 million pounds to 73 million pounds, representing $11 million in lost sales. This case is among the earliest examples of ocean acidification imposing a direct effect on the economy. Unfortunately, we can safely say it is far from the last.

By installing new technology to carefully monitor ocean temperatures and chemistry, some west coast hatcheries were able to rebuild, but their bounty might be short-lived. While temporary mitigation measures have been successful, they are just that – temporary. Scientists from Mexico, Canada, and the United States found that upwellings of acidic water like those that wiped out the Pacific hatcheries operate on a delay of several decades – the water rising from the deep ocean today holds CO2 absorbed approximately 30 to 50 years ago. In the last 50 years, the levels of CO2 in the atmosphere have risen 25 percent – a terrifying presage for the health of the world’s oceans. Burke Hales, one of the scientists involved in the research, explains:

“We’ve mailed a package to ourselves … and it’s hard to call off delivery.”

Benoit Eudeline, chief hatchery scientist for Taylor Shellfish Farms, the largest US producer of farmed shellfish, likened the current situation to “sitting on a ticking time bomb.”

Read the rest of the story on Climate Progress, edited by Joe Romm.