Posted on UTSanDiego.com: 11 Jun 2012 By Mike Lee — Collection of seawater samples sets a baseline for scientists

A wave of research suggests that increasing amounts of dissolved carbon dioxide are altering the world’s oceans, potentially throwing eons of marine evolution into chaos.

But how do scientists track subtle changes in ocean chemistry with the kind of precision that can be compared around the globe and across the decades? It’s a seemingly simple question, yet one with profound implications for tracking some of global warming’s most pressing impacts.

The answer is found in a fortresslike laboratory at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, part of UC San Diego. In the bowels of Vaughan Hall sits a mad-scientist contraption of bottles and tubes that ensures quality control for more than 8,000 reference samples of seawater sent each year to researchers in approximately 250 labs worldwide so they can base measurements of dissolved inorganic carbon and alkalinity on the same standard.

Think of it like the Greenwich Mean Time of seawater research, a cornerstone of global science. Without it, results easily could be skewed by sensitive machinery getting out of whack and spitting out confusing data.

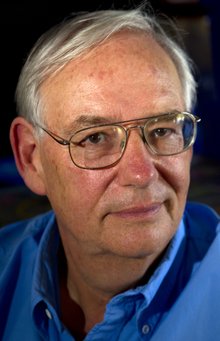

“Before the railways existed, each city across the U.S. had its own time,” said marine chemistry professor Andrew Dickson, who runs the “reference material” program at Scripps. In the same way, he said, “each lab had their own way of calibrating (their instruments) so if people had the same sample, they got different answers. Now, multiple labs in different countries and at different times can put together information that can be compared. That allows you to see changes in the ocean over time.”

Related investigations are critical to better understanding complex interactions between the air, the ocean and marine organisms.

Fossil fuel burning over the past several decades has sharply increased concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The phenomenon was famously tracked by the late Scripps researcher Charles David Keeling in Hawaii and the resulting chart (the Keeling Curve) is a scientific landmark of the 20th century. Though it’s not as well-known, Keeling measured a similar phenomenon in nearby ocean water and was a driving force behind the reference lab at Scripps when he and Dickson realized international oceanography expeditions would struggle without a measurement standard.

“(Keeling) always strove to get the absolute best possible number,” said Guy Emanuele, a Scripps researcher in the seawater CO2 program. “Sometimes, it wasn’t so easy to work for him as a result, but that legacy (of precision) is carried on.”

Today, researchers say oceans have absorbed about one-third of the carbon dioxide caused by human activities. That process changes the chemistry of seawater, possibly faster than organisms can adapt. One widely predicted outcome is that shellfish will struggle to build their homes.

Such concerns have circulated among scientists for decades, but Dickson has seen his business more than triple in the past few years as attention to ocean acidification has spiked.

In a recent review of hundreds of studies, an international science team found evidence for only one period in the last 300 million years when the oceans changed even remotely as fast as they are today.

Read the rest of this story on U-T San Diego.