Posted on Bay Nature: 09 Oct 2013 — By Joe Eaton

Tanner crabs, like this one on the floor of Monterey Canyon, are one of the bottom- dwelling marine organisms being studied by MBARI researchers, to gauge how acidification of ocean waters will impact their ability to form their calcium carbonate shells. Photo: 2002 MBARI.

Like other aspects of climate science, ocean acidification (OA) science has drawn the fire of skeptics. Some have used the findings of OA researchers to argue either that the science isn’t settled or that OA isn’t necessarily such a bad thing.

By way of background, sufficiently acidic seawater can either prevent organisms from forming their protective shells, or actually dissolve shells once they’re formed. Creatures that build their shells from calcium carbonate are the most vulnerable. But variations in shell structure—such as a matrix of carbonate and organic material, or an organic outer layer—seem to reduce the impact. With all that variability in the response of marine organisms, it isn’t hard to cherry-pick the data.

In particular, climate change deniers cite a study by Justin Ries of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Ries measured changes in shell calcification in a number of species, including mollusks (clams, oysters, scallops), echinoderms (sea urchins), and crustaceans (crabs, lobsters, shrimp). Although calcification declined in most of his test subjects, in the crustaceans it actually increased, and was greatest at the highest carbon dioxide concentration tested, 2856 parts per million—well beyond current ocean levels of about 400 ppm, and way beyond anything in even the direst forecasts. (The higher the CO2 concentration, the lower the pH and the greater the acidity.)

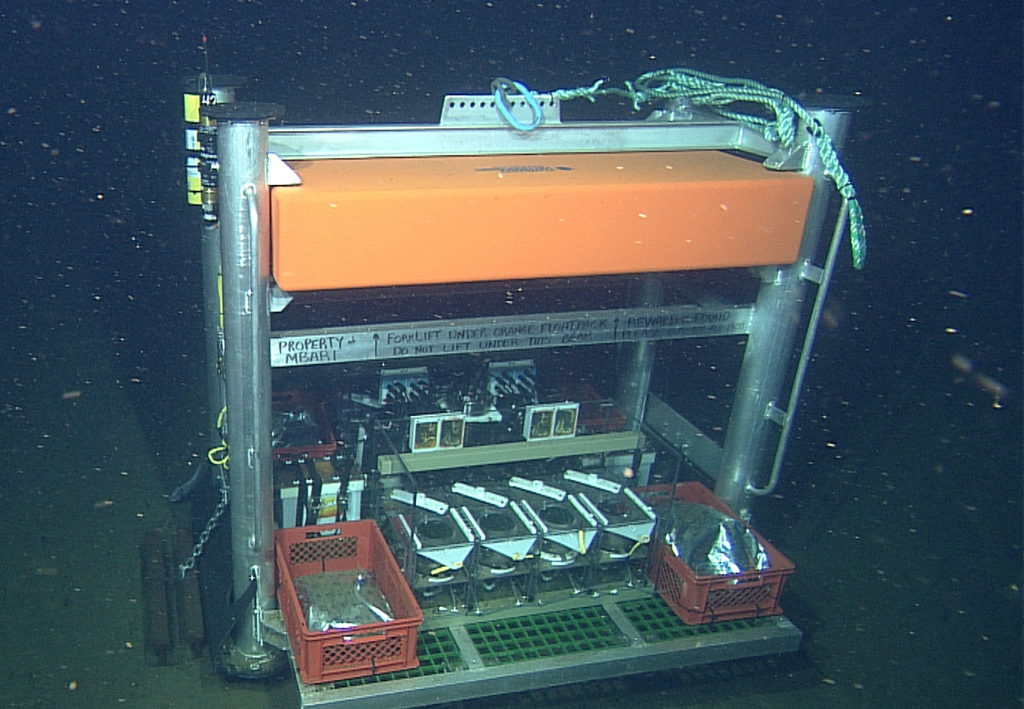

Researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) have been studying the impacts of increased CO2 in the deep marine environment for over a decade. This “benthic respirometer” on the floor of Monterey Canyon has chambers in which a variety of deep sea organisms are exposed to differing levels of CO2 to see how they respond. Photo: 2012 MBARI.

Testifying in US Senate hearings in 2010, skeptic John Everett claimed that “crustaceans build more shell when exposed to acidification… [S]ome species flourish while others diminish. With no laboratory or observational evidence of biological disruption, I see no economic disruption of the commercial or recreational fisheries…” Ries’s response: “The published variability in the responses of marine organisms to ocean acidification should not be misconstrued as evidence of their immunity to it.”

Local scientists Jim Barry of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and Tessa Hill of UC Davis’ Bodega Marine Lab don’t question Ries’s findings. But context is important. In his testimony, Barry pointed out to the Senate committee that those anomalous lobsters may have been harmed in ways that Ries’s study wasn’t designed to detect: “[W]e do not know how ocean acidification might have affected physiological processes other than calcification in these organisms, or how lifelong immersion in acidified waters would affect their growth, survival, and successful reproduction…[W]ould they grow more slowly or produce fewer young to support high skeletal growth?” Barry’s own research shows that some deepwater crabs suffer metabolic stress when exposed to acidified seawater. He also warns that even if the crabs and lobsters got a boost in shell formation, they’d be out of luck if their molluscan prey died out. In the sea, as elsewhere, no species is an island.

Joe Eaton is a land-based writer, although he has been curious about sea creatures since early summers in the Georgia Sea Islands and on the Florida Gulf Coast. Eaton wrote the Bay Nature Magazine article, Ocean Acid Trip: The Hidden Harm of Climate Change, which appeared in the October- December issue.

Read this article on Bay Nature.